Magic is chasing trends, and has been for some time now. I do not think this is a very controversial statement, especially not in light of the announcement that future Universes Beyond sets will be part of Standard tournaments. But it was apparent even before that, with 2024 being an entire year with mostly top-down trope-heavy sets, especially Murders at Karlov Manor and Outlaws of Thunder Junction. It is easy to understand the temptation for designers: a trope set or genre pastiche may capture a built-in audience or crossover appeal. Yet many of Magic’s recent sets in this style are behind the times, in some cases comically so.

Lord of the Rings is approaching its hundredth anniversary, and it’s not very clear how many people still read it for entertainment or how many mainly know it from the movies; still, it’s foundational to modern genre fantasy, so we probably have to go a little easy on that one. Going back a couple of years, one of the early Secret Lairs was Walking Dead and another was Stranger Things, both coming somewhat after the peak of the programs’ popularity. Even some of the upcoming sets that are connected to long-lived franchises like Final Fantasy and Marvel Comics are releasing at an odd time, when there are no major releases planned and/or cinematic universes are in a quiet phase. It’s unclear if Wizards decided to do a cowboy set because of the semi-regular joke among players, the mysterious Redditor Shadowcentaur’s Lorado fan set, or Red Dead Redemption 2; either way, all these things were a comparative eternity ago by Magic development standards. And then, there’s Bloomburrow.

Animal fantasy is a significant part of the canon, with roots in ancient stories like Aesop’s fables, but it hasn’t been prominent for at least twenty years. Brian Jacques’ Redwall series was already past its peak of popularity by the time Magic finished the Weatherlight Saga; and while Mouse Guard is well-received and has a devoted following, it hasn’t hit the same peaks. Watership Down and Charlotte’s Web were influential in their time and space, but nobody really talks about them any more. Like all fiction, animal fantasy attempts to tell us something about the human condition, with the recent entries mostly themed around friendship, courage, and perseverance. They tended to play these themes very straight, perhaps a little too much at times – look at the controversies and arguments related to Outcast of Redwall and its apparent endorsement of essentialism. (People can more easily accept that orcs are “always Chaotic Evil” because orcs aren’t real. Rats, weasels, ferrets, and foxes are real, and people know what they are really like.) This may be why the genre fell off as stories with “gray” morality became more popular, driven by the success of franchises like Game of Thrones and The Witcher. Friendship, courage, and perseverance are not less necessary than they’ve ever been, but specific explorations of them are always subject to rises and falls in popularity.

Bloomburrow feels, at first glance, like they were getting to a trope they simply hadn’t yet done. This is reinforced by the set’s superficial elements: it looks so much like Redwall and Mouse Guard that even the cards that weren’t drawn by David Petersen look like they could be lost covers or pages from at least one of those series. It has a focus on food and friendship that reminds us of the former, and woodland creature industries and guilds that remind us of the latter. This made it even more curious, then, when the Bloomburrow cards and worldbuilding turned out to be the most interesting of 2024.

It has a pleasing inversion from Thunder Junction, where you can scratch the surface and find some original – or at least uncommonly-used – ideas. To quote King Solomon, there is nothing new under the sun (Ecclesiastes 1:9), but the way you recombine, remix, and retell the concepts is everything. Because we view animals as being closer to nature and instinct than we are ourselves, animal fantasy is a surprisingly suitable place to explore themes like the cycles of time and civilization. Redwall did it to a certain extent, and Bloomburrow, surprisingly, does it even more. In my opinion, it handles the themes and moods adjacent to the Ragnarok concept even better than Kaldheim does.

The plane’s underlying connection to these Eddaic concepts is reinforced by the worldbuilding elements related to the Calamity Beasts. Recall that Bloomburrow does not have a natural progression of seasons the way that planes like Dominaria or Ravnica do. Instead, weather and climate are tied to the movements and behaviors of the elemental animals represented by cards like Galewind Moose and Maha, Its Feathers Night. This is most obviously a reference to the literal and metaphorical role of Fenrir, the wolf of Fimbulwinter who eats the old world to make way for the new. And its relevance to the denizens of Valley, animals who have certain human characteristics and thus blur the already tenuous division between humans and other animals, raises other fascinating and relevant questions. As I’ve noted before, reading the Norse myths often leads readers to wonder whether Odin’s attempts to avert Ragnarok actually helped or rather brought it closer. In a similar vein, the animals in Valley have only limited ability to communicate with, interact with, and influence the Calamity Beasts, a relationship which echoes our own society’s struggle to understand and make use of disaster management and climate research.

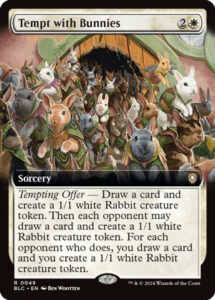

Of course, none of this is part of the main marketing push of Bloomburrow – the mythological elements are quite well developed, but overall, most of the set is very firmly within the genre of cosy fantasy. That is a sentence I never expected to type in the context of Magic. But it is true. Bloomburrow is a faction-based set for the purposes of draft gameplay, but the cards almost all portray those factions co-operating, and the flavor makes it clear that their priority is co-existence; they do not scheme to destroy each other like Ravnica’s guilds do. The art of cute bunnies and bright colors is obviously an even clearer giveaway, and frankly, it is a breath of fresh air in a game that often tries way too hard to be epic and edgy.

I’m sure it’s tempting to write this off as yet another of my idiosyncracies. And yet, there’s a famous Australian game store whose newsletter claimed they had record-breaking attendance at Bloomburrow‘s pre-release. When Mark Rosewater was asked about the likelihood of another expansion using the Bloomburrow setting, he put it in the second tier of most likely/soonest revisits. From another perspective, he put a three-month-old plane, which we have just seen for the first time, at the same likelihood/soonness as Zendikar, and above Theros and Eldraine. Wizards of the Coast spent years trying to hook people into sets with powerful reprints, collector gimmicks, power creep, high-stakes tournaments, and more besides. Apparently, what players actually wanted was bunnies.

And beyond that, Bloomburrow is the only one of the past year’s trope sets that came at the opportune time. You may have heard the term “cosy” applied to various genres of literature in the past few years; it can be applied to almost any genre, and its details vary, but there are always a few things in common. Stakes are often lower: a cosy fantasy story might be about keeping the balance or helping people, but often on a smaller scale and with a focus on themes like fellowship and belonging. Themes can be adult but won’t be overly graphic: a cosy mystery might be about solving a murder, but it will focus on the sleuth’s process and personal interactions with most or all violence and sex occurring off-camera.

Bloomburrow‘s flavor doesn’t entirely fit this description – Maha is as close as the plane has to a god, and Mabel and friends are on a quest to deal with the god’s wrath. But there are no pure genres anyway, and this feature of the set does not detract overall from the welcoming, reassuring, and inspiring mood that suffuses Bloomburrow. Neither, for that matter, do the aforementioned allusions to Ragnarok and Fimbulwinter. The set’s elements manage to fit together, and while it still has too little flavor text and too little time devoted to it in Magic’s release schedule, it has a solid foundation which shows, once again, that Magic’s lore has a great deal of untapped potential.

You might be tempted to ask why it’s so significant that Bloomburrow is cosy. You might even ask whether it’s appropriate to indulge in cosy fiction when there are so many problems in our world. But as I’ve said in this space before, it is a valid question whether the world needs more darkness in it; if all your fiction is dark and you also perceive darkness in the outside world, where do you turn? I’ve heard it said that the apocalypse as it manifests in our day-to-day lives is not destruction – that actual destruction of societies is rarer than we seem to believe, and that while images of it can be cathartic, they also prime us to wait for something which will never come. The argument goes on to claim that the true apocalypse is misery: the feeling that our lives are so pointless, and our worlds so broken and corrupt, that the most relevant response is not even anger but rather apathy. But when you feel that the only available emotion is misery, you risk forgetting how to find the other emotions. When you perceive only darkness, you turn away from the light. When you feel that the world cannot be fixed, you will stop trying to fix it.

Cosy fantasy is reassuring, yes, and this may be its main point and purpose; but all stories are capable of telling us a little more about ourselves and our experiences, if we wish to hear it. It can be argued that the real world is not entirely like cosy fantasy, but it can equally be argued that the world is also not like grimdark fantasy. Think of whatever time in human history that you consider to be the absolute worst, when misery and ignorance were rampant and evil seemed ascendant. I won’t tell you mine, because everyone has a slightly different idea about this, but if you have read history, you will have one in mind. Even during such times, there was still good in the world. And Bloomburrow, like all cosy subgenres, fundamentally reminds us of this: that even when all seems dark, there is still something in the world worth saving.