I was very delayed writing this review because of various real-life stuff – my Mystery Booster articles were also similarly delayed, but are still coming. While we definitely need to break the cycle of rushing and hurrying while somehow still overthinking, I suppose the delay is also rather fitting. Duskmourn‘s entire premise is about being lost in a haunted house that’s grown to the size of an entire plane, unable to find the path you thought you were on or the path you wanted to be on. That last sentence came out darker than I intended; it has been a very stressful few months.

I won’t bury the lede here: I was expecting to dislike the set, given that horror is not generally my number-one genre. I saw a few of the 80s-inspired survivor characters during preview season, and found them genuinely jarring compared to other recent character designs. The set is also a massive tonal whiplash not just from Bloomburrow but also Foundations, both of which are among my favorite sets of the past five years. But Duskmourn has really grown on me. It has concepts which are, at times, genuinely innovative and actually clever, and we have to ask once again why they don’t do these more often.

In general, the illustrations manage to pull off a look that reminds viewers of the high-contrast appearance of TV and movies in the 80s and 90s, where there was a very large difference between the darkest and brightest parts of the screen. While many of them are more detailed than motion pictures of that era were able to be with the cameras of the day, the feeling comes through quite strongly. Once you start looking at said illustrations, there are also a lot of interesting details which hint at mysteries that a set of the blockless era can’t explore. My favorite might be the appearance of moths around Valgavoth and his demonic servitors. This was inspired by an experience from the creative director’s childhood in Guatemala, and the contrast between what readers know about the generally benign insects and the malevolent, all-consuming House can affect you even if you don’t think about it consciously.

The design of the survivor characters is rather hit and miss for me, though I have started to find it slightly less dissonant as time goes by. The issue arises because they are generally so much like the era in which we live – there is no mainline Magic set with visuals and concepts as close to the modern day as Duskmourn. The closest that we’ve gotten so far was Innistrad and the couple of Future Sight cards that hinted at a Victorian-inspired world, which is really saying something. The survivors aren’t just inspired by Buffy and Ash Williams; they actively look like Buffy and Ash Williams. The observation – and the associated arguments on social media – raise questions about what makes a genre what it is, how consistent a particular franchise needs to be or should be, and why exactly people engage with specific genres and franchises. Do we read fantasy to forget about the real world? It’s not possible to do this entirely, because every story tells us something about the human condition and our own world. I also can’t help but wonder if people who reject Duskmourn‘s survivor aesthetics and technology would also criticize writers like Charlaine Harris and Neil Gaiman over their urban fantasy stories – and if they would not, why Duskmourn is different to them.

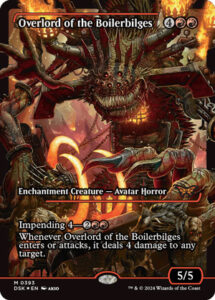

The other side of Duskmourn‘s character design is the monsters and creatures, and for me these are the highlight of the set. When the House gets weird, it gets seriously weird – the enchantment creatures are by and large the most divergent things since the original Kamigawa block. I am genuinely impressed by how well they’ve been able to integrate enchantment creatures into the flavor concepts of Magic over the last decade. They haven’t been a major theme in many sets: most notable the Theros block, Theros Beyond Death, Kamigawa: Neon Dynasty, and now Duskmourn. Yet they have a clear worldbuilding niche associated with liminal spaces and conceptual and spiritual borders, and with warpings and transgressions of mundane reality. This is not a trivial achievement, considering they were introduced twenty years into Magic’s existence, when all such worldbuilding niches could theoretically have been filled. I also find the design of Duskmourn‘s beasties to be very clever. It’s easy to make horror-themed cards inspired by Friday the 13th, Saw, or Ringu. It is harder to make ones inspired by Where the Wild Things Are, and this is another example of the mentality that Wizards of the Coast needs to tap into more often.

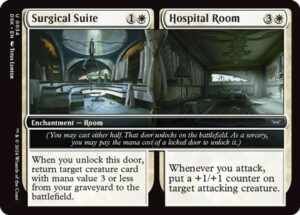

While this is the gameplay-free review, I do need to talk a little about one of the set’s main mechanics, in so far as mechanics can support flavor. I do not think the Room cards work as intended. The concept of a locked door that could conceal anything is a significant horror concept, and it is valid to explore in a game. But now that everyone has, in theory, access to card databases, your opponents could also in theory know what the other side is the moment you play your Room. The sideways orientation of the cards also hinders the impact of the art, making it very difficult to pick out details – a lesson I thought had been learned from split cards. If it’s not possible to actually conceal a room’s contents and we accept that people might in practice know what’s coming, it would have been better to re-use the dungeon mechanic from Adventures in the Forgotten Realms and Battle for Baldur’s Gate. It would fit just as well as Rooms with Duskmourn‘s setting concept, if not better: I have an acquaintance who likes to point out that the whole plane has literally become a dungeon. I find it hard to believe that Wizards of the Coast didn’t notice, and am dismayed that the dungeon mechanic is still (for now) very limited in its options and/or locked to Dungeons and Dragons.

On top of everything else, Duskmourn illustrates the importance of occasionally slowing down and thinking, regardless of what Magic’s breakneck release schedule might encourage. I thought I would dislike the set but ended up rather liking it; you might have an evolving opinion of your own. That’s the nature of things, and it’s something that seems to have been lost in a lot of the online arguments that so hold some people’s attention – arguments which took on an ugly tone previously seen more with Universes Beyond sets. I don’t even read Magic forums any more, and they still filtered their way to me. I think that is another, less conscious reason why this article took so long, because even minor engagement with those arguments is utterly exhausting and demoralizing.

Some parts of the online Magic world have a knack for getting outraged about absolutely everything. At the end of the day, as much as Magic can take on deeper or unintended meanings for people, it is still a product that you are supposed to be buying and playing for fun. If one of its sets doesn’t appeal to you, nobody is forcing you to use it. If someone feels compelled to, for example because they think they can only play with strangers at stores or tournament centers, there is nothing inherent to the cards that compels this – they will still shuffle at someone’s house, and they will still change zones and attack at the park. If your “solution” is to get up and leave a casual table the moment you see a Universes Beyond card (or any particular set) being played, turning up your nose at people who just wanted to play a game with another human being, I would suggest that you have bigger problems than what’s on the Magic cards.

Note that none of this means that Universes Beyond or 80s fantasy is automatically a good idea, either. But there are just as many arguments in favor of both of those things as there are against them, and asking that every Magic fan line up in one of two polarized binary positions is poisonous to real discourse and real play. And it is just plain obnoxious on top of that. Magic fans like to think of themselves as intellectual and open-minded, but some of them behave like the exact kinds of people who they think the game sets them apart from. At its heart, the Universes Beyond and subgenre polarization denies an essential strength of Magic: its diversity and the possibly limitless number of ways the cards can be played with. In many ways, it escaped Wizards of the Coast’s control long ago – yes, they’re the only source of official new cards, but casual play and fan formats are far bigger than anything they’ve ever done, and always have been. The most-acknowledged format, even by Wizards of the Coast themselves, was invented by fans. The next Commander might be waiting for you to invent it. It is our game. It’s time we do something better with it – and with ourselves.